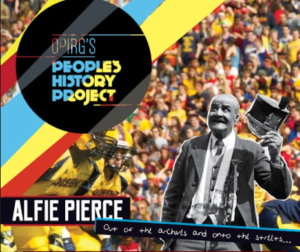

The Story of Alfie Pierce, Black man turned into a mascot

Today we are talking about the life of a legendary character in Queen’s history: Alfred “Alfie” Pierce, and how the university dropped the ball on treating him with full human respect during his life, and fully honoring his memory afterwards.

While many past and present Queen’s students are familiar with the name “Alfie,” few are really aware of the true story. The story of his life and role in the Kingston and Queen’s community gives a window into the University’s controversial past issues with the black community.

Accounts of Alfred Pierce’s life vary dramatically, but according to the traditional story he was born on the Queen’s birthday, May 24, 1874, in Kingston to two fugitive slaves, Margaret and Albert Pierce who escaped from the United States to settle in Kingston. He was christened at St. James’ Anglican Church and attended Gordon Street Public School, which was originally located where Ban Righ Hall, the women’s residence, now stands.

When he was only twelve years old, Pierce is said to have been orphaned and left in the care of his half-brother from his mother’s first marriage, David Dempster, for a short while. However, official records saying the date of Margaret Pierce’s death was in 1903, when her son would have been around thirty years old, contradict that element to the story. We’ll find that, despite his popularity amongst the Queen’s athletic community, many facts about his life are disputed or unknown.

But what is certain is that Pierce was a very talented athlete from a young age.

At only fifteen his talent was noticed by Guy Curtis, football captain and one of the most iconic and successful athletes in Queen’s history, who invited Alfie to the team’s football practice the next day.

After this, Pierce became the waterboy, handyman and masseuse of the team, but was more seen as the team’s mascot. Regardless of whether or not Curtis was indeed Alfie’s patron, Pierce idolized him. In a photo taken of the 1892-93 hockey team, you can see Alfie lying on the floor at their feet, with Curtis’ foot on his hip.

Amina Ally summarizes it well in “Deconstructing the Queen’s Spirit”, describing Alfie as the black “charm piece or object of amusement for the Queen’s football team of white men,”

She points out that “given the historical background” it is “a liberal statement to say that the Queen’s football team had their very own public slave.”

Many saw Alfie as an integral part of Queen’s football and played an important part in the pre-game ritual. Mervin Daub’s book Gael Force: A Century of Football at Queen’s, has a chapter called “A Gentleman of Color” that describes the ritual:

It would start with Alfie standing on the playing field to greet the players, who , led by their captain, ran in a single file line from the dressing room under the stands. He would be flamboyantly dressed in the University’s colours, described as “a tall, stooped, dusky man, with large feet, gnarled hands, and a certain nobleness of countenance and dignity of bearing.”

He would throw a football to the captain, who would then lead his players into a pre-game warm-up.

Flanked by a couple of cheerleaders, Alfie then would shuffle dramatically, as if his feet hurt him, (which they did), to the bleachers on the student side of the field.

Then came the iconic chant that is engraved in the memories of thousands of alumni and Kingstonians.

“What’s the matter with Alfie?” asked the cheerleaders. “He’s alright!” the fans responded.

“Who’s alright?”

“Alfie!”

“Who says so?”

“Everybody!”

“Who’s everybody?” And then the fans would go thundering back the oil thigh.

While the Queen’s Encyclopedia says that “football captain Guy Curtis named [Pierce as “team mascot”] with the thoughtless bigotry typical of the day,” it fails to expand on how racism surrounding “Alfie” continued to be perpetuated long after his death.

_____

Life

Now let’s dive a bit more into the personal life, the side of Alfie that most people don’t know. Alfie was allowed to sleep beneath the stands of Richardson Stadium in the summer and sleep in a change room turned boiler room in the basement of Jock Harty Arena in the winter.

In exchange for the Queen’s Athletic Board of Control’s quote, un-quote “generosity,” Pierce was given the responsibility of acting as both a handyman and night watchman and keeping the furnace full of coal. His only roommate was his co-mascot Boo-Hoo Bear.

According to a biography of Pierce’s life , this arena furnace also doubled as Pierce’s stove for quite some time. In his tiny room in the bottom of Arena, Alfie initially didn’t have anywhere to cook so before going to bed, he would put a can of soup or beans bought at a nearby grocery store on Alfred Street, on top of the hot water boiler and leave it there all night because this was the only way that he could have a hot meal ready for him the next day. Pierce’s acquaintances said that later he was able to get a small stove he could cook his meals on. It was not until later that the Queen’s Athletic Board decided to finally compensate Alfie with a weekly “allowance” of ten dollars, a Christmas bonus and “clean underwear every week.”

Pierce’s biographies don’t have much information about his personal life, but go in depth of his “money-making schemes as an elderly man.” One of these stories talks about, a local merchant who would regularly stop by Jackson Hall after work everyday to chat with Alfie and give him fifty cents.

Alfie never failed to leave whatever he was doing at that time of day and hobbled to the Jackson Hall steps to meet the merchant. Once he had his fifty cents, a very pleased Alfie would return to work.

Pierce would also get gifts of dollar bills in the mail at Christmas from fans in the Queen’s and Kingston community, but would have to wait for the superintendent to come bring him his mail, because he was “discouraged from wandering around the gymnasium complex” where the mail was delivered.

Around Christmas, each year Alfie would look forward to the delivery of the cards and was rumored to give the messages in the cards little attention once he pocketed the cash gifts.

Biographies also describe some of Alfie’s so-called “less legitimate means of acquiring money.” Books go into depth about certain stories like the time a Queen’s Faculty of Medicine prof questioned Alfie about his “shabby attire.” When Alfie told him that he did not own anything else, the Professor “sent over two expensive suits” that he didn’t need anymore. Alfie is said to have “promptly sold the suits for five dollars each.” Similarly, after asking about his scruffy clothes, the owner of a local men’s wear store sent him a fur coat which Alfie once again sold. The criticism of Alfie’s “less legitimate means of acquiring money” is a topic often covered in a lot of detail, yet few have focused on the conditions that made Alfie’s actions necessary.

Given the conditions in which Alfie lived, it should come as no surprise that social etiquette surrounding gift-giving was of lesser importance than fighting to make sure his needs were met.

Some biographers have appropriately pointed out that instead of “buying practical items or necessities, for Alfie, professors and locals chose to get him suits and coats because they felt it was more of a priority that the Queen’s mascot look presentable.”

While there may be some truth to the stories about Alfie’s “money-making schemes,” they are really just a small part of Alfie’s story–and are often given way too much attention. What isn’t given enough attention, however, is the fact that all these supposed “money making schemes” are a symptom of the racism that he endured when he lived and worked on campus.

The focus must shift from a critical analysis of Pierce’s behavior to one that considers what conditions on Queen’s campus made Alfie’s actions necessary.

As research conducted by the Stones Project highlighted, Alfie did not always reside on Queen’s campus, particularly during the years of WWI. From 1906 to 1908, Alfie was listed as a laborer in the directories living on Albert Street and from 1909 to 1912 he worked at the Locomotive Works and lived on King Street East. After that he went from being a hack driver to being a liveryman, moving around from lodging to lodging as his job changed.

When Alfie returned to Queen’s campus after the war years, he shared his accommodations with his bear co-mascot. Queen’s bear cub mascot named “Queen Boo Hoo” lived in the boiler room of Jock Harty Arena for the couple of years it was at Queen’s with Alfie in charge of feeding her. However, Queen Boo Hoo was moved to a zoo in Watertown, NY after becoming “too vicious”.

Some biographers have appropriately pointed out that despite the bear’s viciousness, “none [of the articles written about Alfred Pierce] even bother to explore the consequences of the bear’s violent behavior on Mr. Pierce’s safety.”

In fact, instead of concerning themselves with the safety of Pierce’s living conditions and the dangers that come with having a bear for a roommate , the Board instead chose to replace Queen Boo Hoo with a series of six black bear mascots each successively named “King Boo Hoo.”

_____

Decades later, in 1948, Alfie had a stroke that left both of his arms paralyzed. He had a second stroke in 1951 and was found unconscious on the floor of his room in the arena. According to one account, “hospital officials said he also suffered severe frostbite to both feet which had become gangrenous.” He died shortly thereafter. After his death, Alfie Pierce’s body lay in state in the gymnasium for two hours as students, staff, faculty and alumni filed past. Four former football captains and two recipients of the Alfred Pierce Award, created during his lifetime and presented to the top male and female athletes in first year, were the pallbearers. Alfie was buried in the Church of England Cemetery at Cataraqui near his mother. His gravestone, a gift of the Class of Medicine 1934, bears the following inscription:

Alfie Pierce

1874-1951

A faithful servant of Queen’s University

Erected by Meds ‘34

This “faithful servant” is often remembered as the personification of Queen’s spirit and the name Alfie Pierce has come up many times on campus since his death. Some believe that he never left and his memory has often been used in Queen’s folklore. In the 1970’s, the Queen’s Journal and the Whig-Standard published articles claiming that Alfie Pierce’s ghost had come back to haunt Queen’s campus.

When a student was found dead outside the alumni office, a Queen’s Journal article blamed the ghost of Alfie Pierce.

In 1975, one letter to the editor published in the Queen’s Journal and signed as “Alfie Pierce” and explained the reason given for the supposed retaliation of Mr.Pierce’s angry ghost was the unimpressive 1974 Gaels football season.

Another article published by the Whig-Standard in 1989 described a show during a two-day festival celebrating Cataraqui heritage where an actor playing the part of the “ghost” of Alfie Pierce “[appeared] from beyond the monuments and [joined] the crowd”. There are several articles published in both papers that have dramatized fake stories of Alfie’s ghost and created an amusing perception of Alfie and his life.

_____

In 1979, there was a vote to decide the new name of the campus pub under the JDUC (which is now know as the underground). The three options were Alfie’s, the Underground and the Crumpled Kilt. Although in the 70’s the name “Alfie’s” won by a landslide, the choice was later questioned.

In 2006, the chair of Culture Shock, a campus publication that is still published in Collective Reflections every year, organized an event called “Free Alfie’s.” This coffee house style event attracted about 150 members of the Queen’s community. Pins that read “Free Alfie’s” and “Respect Mr. Alfred Pierce” were sold and played an important role in creating a dialogue to help students learn about Alfred Pierce.

In an article, Amina Ally called for the name of the campus pub to be changed. She said:

It is crucial for us to educate ourselves regarding the unspoken history and blatant racism behind the Queen’s tradition. It is also crucial for us at Queen’s University (students, staff, faculty, administration and alumni) to be committed to concrete action. Thus, knowing the background regarding “Alfie’s” campus pub, and understanding the following action needs to be taken concerning what this “strong tradition at Queen’s” really means and what “the spirit of Alfie Pierce” truly represents. An important and symbolic anti-racist action this institution can commit to is to change the name of our campus pub. This kind of action is long overdue and our inaction simply confirms the anti-racist reform policies and statements echoed over many years of lip service.

In 2013, the name of the campus pub officially changed from “Alfies” to the name it has now, “The Underground.” The AMS vice-president of operations at the time, Nicola Plummer, told the Queen’s Journal that the name change was “a result of concerns raised by students that the club negatively reflected on the memory of Alfie Pierce.” Plummer pointed out that “[The Underground is] a non-offensive name that reflects [the venue].”

However, measures should be taken to ensure that the reasoning behind this name change is remembered, because erasing Alfie Pierce’s story does not change the history of racism on Queen’s campus.

Biographer Amina Ally summarizes it well, explaining that:

“Alfie’s treatment by Queen’s is an example of how members of a dominant culture failed- and still fail- to see how their treatment of a marginalized person robbed him of autonomy and dignity.”

The story of Alfie Pierce is a story that illuminates the racist history of Queen’s campus, while the manner in which Alfie Pierce is remembered highlights the ways in which this racism still exists. And yet, Queen’s continues to do all that it can to erase these histories from public knowledge. For example, in 2018, student social justice groups on campus were looking for a safe and accessible office space. Once the space was designated, the groups suggested that it should be named ‘Alfie Pierce Social Justice Center’ to honor this story, as well as Queen’s fraught history regarding racism and racial injustice. However, the administration decided to call the space ‘The Yellow House’ instead–seemingly, in order to honor the color of the exterior of the building.

Many feel that “Alfie Pierce was, and is tradition,” but perhaps this is one tradition that requires a bit more critical reflection. And this is the kind of work we hope to do with the People’s History Project.

Thank you for tuning into this episode! If you would like to hear more untold stories about people fighting for social justice in Kingston, tune into the next episode of People’s History Podcast!

Written by Erica M, 2014. Edited by Finn H and Samara L.

Works Referenced:

Alumni file at Queen’s University Archives

Stone’s Project, “Black History,” online: http://www.stoneskingston.ca/

Amina Ally, “Deconstructing Queen’s Spirit,” PHP Archives (Black History), originally published in Wahenga in 1994

Mervin Daub, “A Gentleman of Colour,” in Gael Force: A Century of Football at Queen’s, PHP Archives (Black History)