“Save Our Prison Farms”

Carceral Labour and Civil Disobedience in Kingston

On August 10th 2019, International Prisoners Justice Day, an organization called Evolve Our Prison Farms (EOPF) was gathered at 1225 Centennial Drive. They were protesting issues around the newly reopened prison farms at Collins Bay and Joyceville Institution.

Almost exactly 9 years prior, on August 8-9th of 2010, a two-day blockade took place outside of Collins Bay institution to save the cows from being removed from the prison. This was organized by community stakeholders such as Save Our Prison Farms, the National Farmers Union, and OPIRG. They were protesting the closure of prison farms at Joyceville and Collins Bay institution by the Conservative government.

Indeed, Kingston has a rich history of activism around the issues of prison farms. While in 2019, groups such as EOPF are trying to raise awareness about how the newly reopened prison farms would be operating on an industrial, for-profit model, unlike how they operated previously.

Image above features a cow with the title of the article, and the OPIRG Kingston People’s History Project logo.

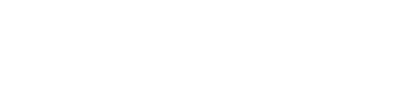

Image to the left depicts an activist being detained by Kingston police, he is wearing a shirt that says “Save Our Prison Farms”.

The lessons learned from 2010 about stakeholders, community engagement, and civil disobedience, remind us that organizing is often tumultuous, with many pros, cons and unexpected occurrences. Groups such as EOPF can learn a lot from the history of prison farm activism that preceded it. And so, here is the history of Prison Farm organizing that took place before the closure of the farms in 2010.

The closure of the prison farms in 2010 brought multiple large community stakeholders together in protest. One of the community stakeholders, perhaps the oldest, was the National Farmers Union. “A lot of the core group of people involved [were] farmers, and that’s how I got involved,” recalls Aric McBay. “The National Farmers Union, and its predecessor organization in Ontario – the Ontario Farmers Union – has from the beginning in 1952 had a very feminist approach; it was required that at every level of decision-making there would be both men and women represented, which most organizations still do not have, […] the organization was about empowering people and their communities […] connecting people to make change.” The NFU, as McBay explains, has been particularly active in the counties of Frontenac, Lennox and Addington, and it was the farmers of those counties that served as the nucleus for the organizing that took place.

The NFU, in the ten years preceding the prison farm movement, had run a series of awareness campaigns to inform the public about how their food was grown, and the challenges farmers were facing. These included Food Down the Road, The New Food Project and Feast to Fields. The importance of this early organizing in the 2000s, as Mcbay points out, is that it allowed for the NFU to create a foundation and networks that were so crucial to organizing around the prison farms.

As he iterated, “While previously the projects that the NFU had done [were] more low-risk projects and were able to engage and connect a lot of people, as the prison farm campaign proceeded, we were able to mobilize people into, what felt like, higher-risk and more confrontational situations”. The presence of the National Farmers Union, and their experience with organizing in the Kingston area, was of the utmost importance for creating a coalition with the greater Kingston community that brought even more people into the fight against the closure of the farms.

The backing and momentum of the NFU was instrumental in creating Save Our Prison Farms (SOPF), which was very active throughout 2009 and 2010, until the final closing of the farms in August. As Dianne Dowling, NFU, SOPF and current prison farm panel member recalls, the closing of the prison farms back in 2010 was hostile towards farmers, because of the Harper Government’s argument that prisoners couldn’t learn valuable skills from prison farms. Farmers were also concerned because the farmland used for the prison farms was ecologically valuable, and the destruction or development of that land would be a real loss.

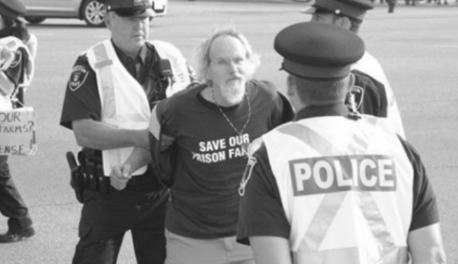

Donkey with a sign on it saying “Conservative Prison Farm Consultant”.

Activist standing next to the donkey is wearing a shirt that says “Save Our Prison Farms”.

As a group, there were 3 things that the SOPF asked of the government. As Dianne Dowling recalls, “first that they put a freeze on closing the prison farms, secondly that they release all the financial information relating to the prison farms (because the government claimed the prison farms were losing $4mil/year), and thirdly we asked for a full assessment of the prison farms”. “We did everything you’re supposed to in a democracy – petition; write letters to editors Ministers, MPs, and the Prime Minister; present to the House of Commons, and so on, but none of these things changed what the Government was saying. People were pretty frustrated and disappointed in what they thought was the best way you could change people’s minds.”

Despite the tangible public outrage, the campaign against the closure of the prison farms is memorable in that it “kept a lot of respect from the community,” says Bridget Doherty, who works for the Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul, and is a member of the current prison farm panel. As Doherty recalls, “It was always, always a respectful campaign” that had “support from all political parties – even the conservatives, it was across the political spectrum.”

The groups that supported the fight to save the prison farms were varying in cause, bringing together not just farmers, but different stakeholders concerned with different issues, as Doherty recalls, including “prison rights groups, people who cared about rehabilitation, but on the other hand [the campaign] included people who felt that inmates should work hard and should contribute to the system, as well.”

The planned closure of the prison farms, despite wide support from people across Kingston, was indicative that the Conservative government did not care about what folks had to say. As McBay recalls, at the beginning of the campaign, there were a “series of small protests that took place, some outside Pittsburgh institution, and then a series of town halls in Kingston […] that helped build public awareness over the span of 14 months, but early in 2010, that’s when things began to really escalate.”

Kingston Penitentiary, with signs hung on the fence saying “Stop Super Prisons” and “Save Our Prison Farms”.

One of the first events marking this new turn in escalation happened on June 6th, 2010 when over a thousand Kingstonians gathered at The Spire to talk about the closure of the prison farms, and then proceeded to walk to Corrections Services Canada in protest. This event featured Margaret Atwood, but what truly made this event memorable is that it was the first event where civil disobedience as a tactic in organizing was discussed. Presenting a speech at the event, Aric McBay pointed to the need for civil disobedience during this time where the government was refusing to be held accountable, and pointed to the historical use of civil disobedience in the suffragette movement, the fight for India’s independence, and the civil rights movement. All serving as proof that civil disobedience has a fruitful way of enacting change (Aric McBay’s June 6, 2010 script at Sydenham Church).

At that rally, people indicated on a form being passed around whether they would like to take part in civil disobedience, whether they wanted to receive training in how to do it properly, and if they wanted to be contacted in an emergency where volunteers would be needed, for example, if a blockade would suddenly have to be made outside Collins Bay or Joyceville in situations such as when prison farm equipment was being removed. From that June 6th rally at The Spire, 500 people indicated that they would like to volunteer in civil disobedience. “I was shocked that we had that many signatures”, McBay recalls. “As an organizer my job is not to tell people what to do, my job is to say, ‘here’s the risks, here’s what we know, do you want to take these risks together?’… my job is to encourage and support”.

McBay’s role, as he says, was to “build up that sense of confidence and capacity, so that people could take action and not go straight from sitting in a Church listening to people talk to facing off with riot police, because that could [have been] very intense if they weren’t ready for it ”. To prepare people and inform them of the risks, two civil disobedience training sessions were held where people could practice being in a blockade, getting dragged by police while also receiving information on what to expect if someone got arrested. The informed mobilization of Kingstonians during 2010 led to the climax of the prison farm campaign over a 2-day period in August, when hundreds of people gathered in an attempt to block the cows being removed from Collins Bay.

Image featured is of cows grazing in the Kingston Penitentiary prison farm.

The mass mobilization of Kingstonians, and the varying groups and political beliefs present throughout the prison farm campaign, is something to reflect more on and what it inadvertently means, Sean Haberle, then OPIRG Coordinator, explains. As he says,“a lot of people came together to fight against something, which doesn’t happen here very often. To have the town ‘feel its oats’ was important, but then again, I think it reinforced [in peoples’ heads] that you can’t win, even when everyone’s against something – and that’s not true – there are examples all over the world, the federal government doesn’t always get what it wants, it’s all about what you are willing to do to make sure the Federal government doesn’t ram shit down in your community”.

The act of rallying ‘the left’ in town leading up to August 2010 highlighted problems of how people like to organize in Kingston. When Margaret Atwood came to lead the march to CSC headquarters on that June 6th rally, Sean remembers it as being pivotal in realizing “how sheeple everyone was; once she marched there were so many people marching who probably wouldn’t have otherwise – people here are followers, and looking for charismatic leaders all the time”.

The rallying of the Kingston community was instrumental during August 8th and 9th, 2010 when civil disobedience was used by participants in the final stretch of the campaign, where organizers and participants gathered to block the cows from being taken away from the Frontenac institution. “People were angry and wanted to do something”, Dianne recalls. They were blockaded for a while, but “we allowed the trucks to go in – I guess that was the beginning of the end – they loaded [the cows] the next morning, and when the trucks came out they were not really impeded by the demonstrators”. The final attempt in the prison farm campaign was to buy the cows taken out of Frontenac to be auctioned off. The Penn Farm Coop was set up by Save Our Prison Farms, with the help of OPIRG, to keep the money accountable that was used to buy the cows from the prison farms.

The cows were to be auctioned close to Waterloo, “most of the cows went to that auction, but there were [some cows] that couldn’t be transported as far as Waterloo, so there was a second small sale of cattle at Selby, north of Napanee. Within days of the cattle being trucked out, we raised $30,000 to buy some of the cattle back. People were really shocked and angry at the cows being gone, and they wanted to do something”. She continues, “we sold shares in the Penn Farm Herd Coop for $300 per share; we sold 100 shares within a week, so we used that $30,0000 to buy around 24 cattle”. As McBay discusses, the focus on the cows but it wasn’t a focus of his that cows became the central focus during and after this blockade, “the status and rights of prisoners, the protection of land was all so important. But the prisoners, at that point, didn’t feature in the public dialogue because of that focus on the cows and because a lot of [the prisoners] had been banned from showing up, so I wish that had turned out differently”.

Image featured is a group of protestors standing outside the Feihe Milking Plant, holding protest signs. Signs include slogans such as “Evolve our Prison Farms”, “No Prison Goat Dairy”, “Rehabilitation Not Exploitation”, “Prisoners Justice Day”, “Prisoner Justice, Animal Justice, Environmental Justice”, and so on.

During the 2 days, 24 people were arrested for attempted mischief while participating in civil disobedience. But, not everyone had equal opportunity in engaging in civil disobedience during this 2-day protest. As McBay explains, “we wanted to make sure that this wasn’t a group of people who were acting upon the behalf of someone else without engaging with them. We had former prisoners at our meetings… but these people, some of them are on parole for life, so their parole officers were like ‘we better not see you out with these protesters or at these meetings, or you’re going to go back to jail… and that made it really hard to do that, especially in a public way, because of the fact that someone going to jail, that’s a big risk – it’s not like just sending someone from the night .”

While prisoners were unable to participate in the final stretch of the campaign during August 8th-9th, it’s also important to note the absence of more explicitly radical groups from the prison farm campaign. As Haberle recalls, “a lot of radical people were super against it, radical vegans were against it, it was a difficult campaign to get ‘the radical left’ on board with; most of them didn’t give a shit because it was too reformist about a terrible system”. Looking back, Haberle says that the campaign was brought together a “lowest common denominator” [of varying political beliefs], but that was also its strength”.

There needs to be a “much larger populist conversation about what prison is,” says Haberle. “Having empathy for people in prison… there’s some really fucked up questions about prison, no doubt about that…but there’s lots of people who are just rotting in prison for a mistake they made a long time ago. Nobody likes to talk about that, it’s taboo, but if you speak in a way that is empathetic towards prisoners, they throw examples of pedophiles and rapists at you to make you stop talking. It’s about having a larger societal conversation about what it means when someone does something bad in their community, and how we deal with that. There’s not a social space to have those conversations publicly. It’s about having the space to have grown-up, logical conversations about people who do things that are fucked up”.

Poster featured says “Save Our Prison Farms For The Common Good”.

Since the closing of the prison farms in 2010, Corrections Services Canada changed its food supply system. Whereas back then, prisoners were drinking their own milk that they made from their prison farms, now that option is not available due to the ‘for profit’ model of the reopened farms. As Dianne says, “right now there doesn’t seem to be any sense that the milk could be kept within the prison system, as it was then”. On its blog, CSC says that “implementing national supply arrangements and standing offers for purchasing food items has led to cost savings”. As it stands, the milk made at the reopened prison farms “will be sold through the Dairy Farmers of Ontario, into the general public market. It won’t be a huge amount, a herd of about 32-35 cows”.

Bridget and Dianne both sit on the Citizens Panel, an advisory board to CSC created in the spring of 2017 for the reopening of the prison farms, consisting of 7 people – 4 farmers, someone from John Howard society, someone from Sisters of Providence, and someone from the employment field in Kingston. The citizens panel made the reopening proposal in fall of 2017, and spring of 2018 was when the federal budget included $4.3 million to re-establish the prison farm. As Dianne explains, it was to the panel’s shock that their plan did not include cows.

“A week after we found out about the budget money, we found out the plan was for crops, land stewardship and goats – no mention of farms. We were given a certain amount of time to submit a proposal detailing how cows could pay for themselves basically.” In June of 2018, they made the announcement that cows would be coming back, as well as goats”. Cows should be milking by Spring of 2020, and goats by 2021, at Joyceville Institution. Bridget says that the new model is valuable because “if [there’s] a model that doesn’t cost the government extra money, then it’s harder for any new government to come up and close the farms – if we want to protect the farms, working with industry and having a public-private partnership in this case is a positive thing”.

Should those that are incarcerated be the target of austerity measures, profit and cost-saving schemes? While in 2010, a large amount of Kingsonians rallied to protest the closing of the prison farms, only a much smaller (and more radical) group of people have questioned the explicit role of profit and incarceral labour in the reopened prison farms. Evolve Our Prison Farm’s spent International Prisoners Justice Day 2019 outside of the Feihe Milking Plant that was being built. Feihe specializes in creating baby formula, from both cow and goat milk. Though there is no contract between Feihe and CSC, their timely arrival to Kingston (their first Canadian milking plant) is nonetheless suspicious. Evolve Our Prison Farms is a movement that’s critical of the for-profit prison industrial complex. Unlike the prison farm campaign that took place in 2010, the organizing Evolve Our Prison Farms is doing requires a level of anti-capitalist, anti-incarceration sympathy. How much their mission is embraced and joined by Kingston over the next upcoming years will be indicative of how much the ‘left’ in this town has evolved, or stayed the same, over the past decade.

Written by Samira L., August 2019. Edited by Finn H.

Works Cited:

https://www.lte-ene.ca/en/highlights/2016-05/modernizing-food-services-csc

https://nfuontario.ca/new/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/500-Citizens-Successfully-Block-Prison-Farm-Cattle-Trucks1.pdf

https://www.foodprocessing-technology.com/projects/feihe-international-baby-formula-plant-kingston-ontario/

See also:

“Til the Cows Come Home” (2014), Directed by Lenny Epstein. https://vimeo.com/97536245

https://evolveourprisonfarms.ca/

https://nfuontario.ca/new/locals/local-316/

https://www.facebook.com/SaveOurPrisonFarms/